Crabbet Arabian News

July 17, 2017

Guttural Pouch Mycosis

July 28, 2017Bygone Era – Riffayal & Sind

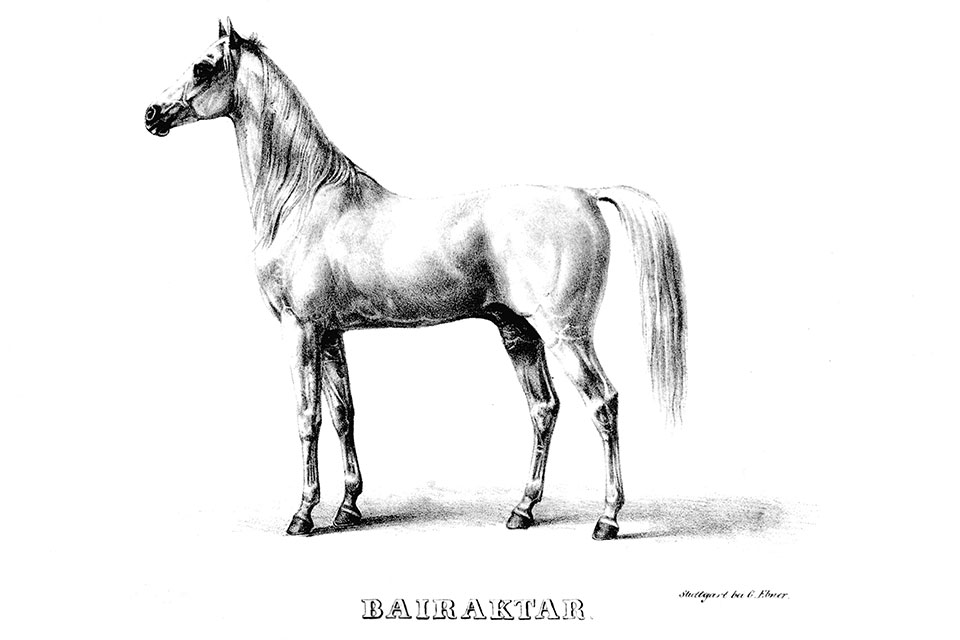

Riffayal and Cecily Crozier at Sydney Royal circa 1952. Photo: Harold J. Pollock

Brian’s Ride to London

A poignant true story for horse lovers everywhere! Waiting at the hospital a few weeks ago, Hastings Online Times’ Zelly Restorick admired the jaunty tartan trousers of the man sitting next to her; they ended up chatting and the man, Brian Cutler, told her a story from his youth, which touched her heart to the core. Here is Brian’s account of what happened – and the recent synchronistic finale.

‘The story started one day back in 1946 in the village of Aldridge in Staffordshire. As a young man of 16 years, I looked after our stud of Arabian horses, in between milking a small herd of Guernsey cows. My work also included feeding pigs and poultry and cultivating 45 acres of arable land.

Early one morning, I was grooming one of our stallions, a handsome dapple grey animal, Riffayal, one of three we had at stud at that time. My father looked over the stable door, saying: “I don’t think that horse looks at all fit and from what I can see, you’ll never get him fit enough to compete at the International (the International Horse Show, being held at the White City Stadium in London).”

I resented this remark and shouted after him: “In my opinion, he’s fit enough to walk to London, never mind being taken there in the horse-box.” To this remark, my father replied, “I bet you a fiver you couldn’t walk him there.” With that, he walked off.

The seed was sown. I planned the journey, contacting farms and hotels along the route who were able to put up a horse and rider. I did my research, planned the route, booked all the accommodation and on a sunny July morning at 7am, my father dropped me off on the busy Stone Bridge Island near the Stonebridge Hotel, which was situated on the Birmingham boundary. My journey commenced.

I was on the way complete with rucksack and all my gear. I suddenly felt very alone and vulnerable; the road was very busy and I felt Riffayal shared that fear with me. Our first day was 20 miles and I stayed the night at the Home Farm in Gaydon. After a hearty breakfast, I set off for the next stop, Banbury, where I was to lodge at the Kings Arms in the middle of the town. Before my arrival, they had to clear the coal out of one of their old stables to accommodate Riffayal.

Whilst in the bar that night, I started a conversation with an American lady, who was returning to the States the next day. Whilst talking to her, she said she wanted to sell a portable radio; it had a long shoulder strap and I thought it would be great to put round Riffayal’s neck, although it was quite bulky because of the size of the batteries. It was early days for portables. Anyway, I thought it would be another first: surely nobody else had or would listen to music whilst you work on a horse on the London Road.

The next stop was Aylesbury and I was to stay at the County Farm, which was an agricultural college for young farm students. I had a great welcome here and great interest was shown by the students and management. Before I left, I gave the students and staff a dressage demonstration; Riffayal had been schooled to do all the high school movements and it went down very well.

The next day’s ride was to Denham, the lovely village famous for being the setting for many films. In Denham, the horse was stabled at a Mr RJ Weekes’ farm and I stayed at the farmhouse, Green Man Pub.

That evening I took a taxi into London and went to the theatre. I only had my riding breeches and boots to wear and I stood out amongst the audience. I could only get a seat right at the front, which made me stand out more than I liked. My embarrassment was heightened, when a comedian on the stage said during his act, “What I’m saying is fact,” pointing at me and saying, “It is right you know, ask Gordon Richard sitting down there.” (Gordon Richard was a famous jockey of the day.) I arrived back at the Green Man to find they were having a lock-in and we drank till the early hours.

The next day I did not feel so bright and the journey facing me was along the very busy dual carriageway, Western Avenue. By this time, I had attracted a lot of media attention and was repeatedly stopped by police, TV and radio.

Every time I was stopped, I was obliged to give a small demonstration of Riffayal doing the Spanish walk – a high school movement which entails the horse high stepping. Riffayal was very highly schooled and delighted in shaking hooves and going down onto one knee.

Very late that last day, I turned into the big gates of White City Stadium to a great reception. The next day, I took part in the class for the best Arab Horse under Saddle and obtained a second prize. He was competing against the cream of the Arabian world, so to us it was the equivalent of a silver medal at Chelsea. I stayed in London to compete in the Arab Horse Show at Roehampton Polo Ground and it was here that my romance and friendship that I had had with Riffayal since he was a foal came to an end. I was approached by an Australian girl, the daughter of a wealthy sheep farmer, who wanted to buy Riffayal with her pocket money. Editor’s note: this was Cecily Crozier – now known as Cecily Cornish, the Patron of the Arabian Horse Society of Australia. I referred her to my father, who arranged to sell Riffayal for 500 guineas; my father was a dealing man.

The deal was struck and I cannot tell you the depth of despair I endured when the time came for Riffy and me to part. I took him to the King George V docks and watched the crate rising into the air, lifting him on board. My last glance of my horse was his head sticking out of the crate; it will stay with me forever.

However, the story did not end there. Riffayal arrived in Australia to go on to win at the Royal Melbourne Show. And recently, out of the blue, I was contacted by the girl who bought him; she’s now 86 years old. She is president (sic) of the Arab Horse Society in Australia and a book has just been written about Riffayal’s success as one of the pillars of the Arab Horse Society in Australia and that he went on to sire many champions. In fact, he died a hero of the Arabian horse world.’

Reprinted with kind permission from Hastings Online Times. Please visit their website at hastingsonlinetimes.co.uk

Splendours of the Past

Alexia Ross revisits the story of a horse that could turn his hoof to anything. Splendour of Sind (aka Plennie) is a name that requires a lot of living up to. It is probable that Plennie’s breeder, Alison Hardcastle, was simply confident in his classic Crabbet breeding and certain of his ability to make a mark. This smart bay colt arrived in Norfolk, England in 1966 and became something of a legend in his own lifetime.

Splendour of Sind was sired by the stallion Shifari, who competed in Point to Point racing in England and from whom he undoubtedly inherited his love of jumping. His dam was the pretty bay mare Scindia and she also produced the stallion Scindian Magic. Scindian Magic was an outstanding sire in the United Kingdom of both purebred and Anglo Arabians but is probably known in Australia for producing the champion mare Sheer Magic and the stallion Scindian Mutiny – both exported there.

In fact, this family is rich with Australian connections. Scindia’s dam was the mare Senga, a full sister to Stefan who breeds on strongly in Australia through his grandson Sarafire in particular. Sarafire was highly thought of by both Crabbet and general performance Arabian breeders, transmitting strong, deep bodies and a great work ethic valued by endurance riders in particular. The best known of all these full siblings was undoubtedly the great mare Silver Crystal, whose influence worldwide could fill an article in itself. It was her grandson Silwan who brought her branch of the family to Oz and he continues to exert huge influence in both Pure Crabbet and High Percentage Crabbet breeding, underpinning many studs that have made their mark supplying top-notch endurance horses.

This was all in the future of course when Plennie was sent as a four-year-old to the Roberts family in the south of England to see if he could make his mark under saddle. His boundless self-confidence meant he would tackle anything. Ursula and Charlotte Roberts quickly understood how to get the best from this big personality. He remained firmly convinced for the rest of his life that he was the one who knew all the answers but he graciously allowed Ursula and Charlotte to learn from him!

It all started conventionally enough. Plennie was shown in-hand and under saddle as a gelding, achieving British National Champion in-hand in 1970 and 1974. In 1975 he managed a unique double, winning both the in-hand and the ridden championship.

He went on to be an ambassador for the breed with constant appearances in public from demonstrations at pony club branches and riding clubs to competing in virtually all types of open classes in showing. In his long and varied career he won over 600 prizes in working hunter, riding horse and ridden Arabian classes plus in horse trials, hunter trials, dressage, combined training, show jumping, in-hand, side saddle and gymkhana. In addition he won in private driving and driving marathon classes. For four years running he won the Dinsdale Trophy for the most versatile Arabian horse in Great Britain. In today’s world he would have picked up a WAHO Trophy.

The driving started because he had done everything else. Plennie was initially indignant at being restricted between the shafts. It took a little time to adapt but he learned to love showing off in his trap. The only issue was he knew that after receiving a rosette it is customary to canter round the ring and absolutely nothing was ever able to convince him that this was wrong in harness. This resulted in a distinctly undignified and perilous exit at the end of every class much to the crowd’s amusement. That was Plennie for you; hugely talented but determined to do things his own way.