Saddle Horse Tips

July 3, 2017

A Bygone Era – Delos & Abiram

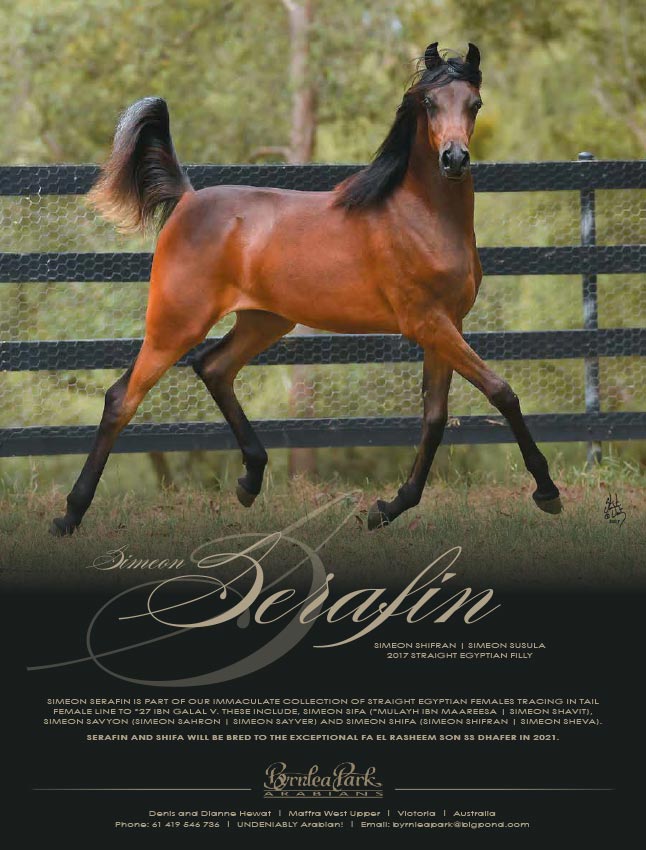

July 5, 2017Lavender Foal Syndrome

Testing for genetic disorders helps produce healthy foals

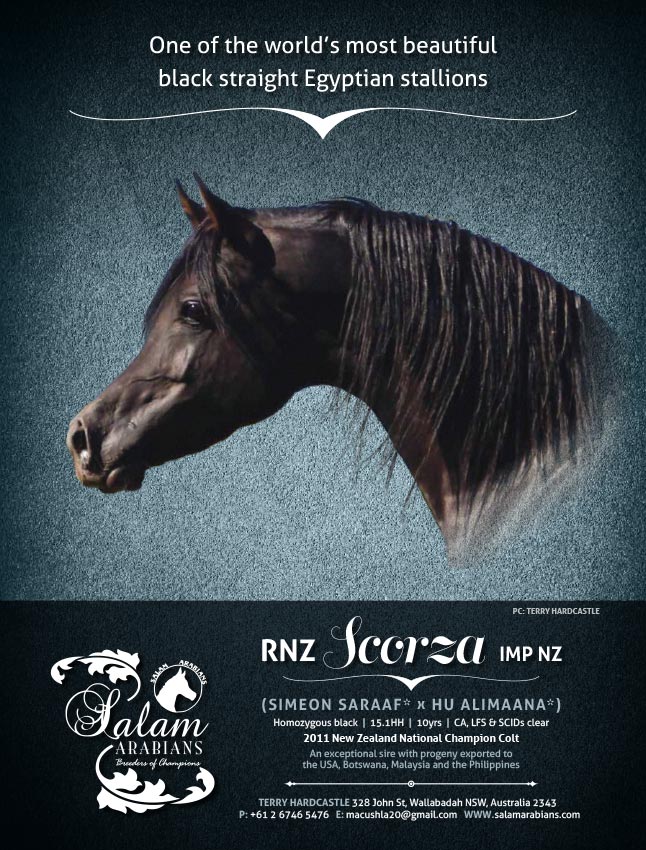

Lavender Foal Syndrome (LFS), also sometimes referred to as Coat Colour Dilution Lethal (CCDL), is an inherited disease specific to Arabian horses. It is caused by a genetic mutation, which is estimated to be present in about 10% of Egyptian Arabians, but has also been reported in other lines of Arabians. [1]

Affected foals are unable to stand at birth, often have seizures and do not improve over time. There is no treatment available, which means they need to be euthanised within the first few days of life to prevent excessive suffering.[2, 3] The good news is that the underlying genetic mutation has been identified and commercial testing is available in Australia. Both mares and stallions can be tested prior to breeding to avoid combinations likely to lead to foals born with LFS. Clinical Signs

The name of the condition refers to a unique coat colouring of affected foals that has been described as pale chestnut, pinkish, iridescent silver, pale slate grey or lavender hue.[2] While Arabian foals can be born with a roan coat, this can be differentiated from LFS by looking at the individual hair. In roans, pigmented and white hairs are both present, whereas in foals affected by LFS all hairs have the same pale, dilute colour.

In the LFS cases described in the scientific literature, no abnormalities were noted during the pregnancy and foals were born after normal pregnancy durations. While some foalings required intervention, other foals were delivered without assistance.[2, 3] Once born, foals with LFS exhibit neurological signs such as an overarched rigid neck, seizures, rigid legs, uncontrolled paddling movements with their legs and an inability to stand or even turn into an upright position. Their suck reflex may be weakened or normal and some foals show rapid involuntary eye movement. Touching the foals can trigger seizures/cramps. Affected foals do not have a fever, but may have elevated heart and breathing rates. Blood tests usually show no abnormalities other than, in some cases, slightly reduced protein and glucose levels. Post mortem examinations after euthanasia do not show consistent abnormalities.

So called “dummy foals”, which experience a lack of oxygen during foaling may also have seizures, but usually lose their suck reflex and typically start out healthy directly after birth. Most importantly, 80% of “dummy foals” recover within three days after being born, while foals with LFS show no improvement in this time frame.[4] Foals affected by septicaemia (blood poisoning through bacteria) are usually not affected directly after birth. They will show inflammation on their blood profiles and likely also bacteria cultured from their blood. While they may be unable to stand up and shiver, they do not typically show seizures.[4]

Another disorder seen in Arabian foals is occipitoatlantoaxial malformation (OAAM), in which skull and spine deformities lead to neurological signs. Finally, hydrocephalus (fluid accumulation in the head), trauma and metabolic problems can also cause similar symptoms.

Causes of the disease

In 2010, researchers in the US found a mutation in myosin 5a to be responsible for the symptoms displayed by foals with LFS. It is a transport molecule that is present in cells responsible for pigmentation of the skin and in nerve cells.

To understand how the mutation is inherited, it needs to be understood that each parent has two copies (alleles) of every gene, but only passes one of these copies on to their foal. Since LFS is recessive, only foals that inherit two defect copies of the gene will develop LFS. If they inherit one defect and one healthy copy, they will be carriers of the disease without showing any symptoms. However, if a mare is a carrier and gets bred to a stallion who is also a carrier, they each give one of their copies (which one is pure chance) to the foal, so the foal can end up being clear (25%), being a healthy carrier (50%) or developing LFS (25%; refer to Figure 1). On a practical example, if Arabella, a six-year-old mare, who has one healthy and one defect copy of the myosin gene (clear/LFS) gets bred to stallion Bartolomeo, also a carrier (clear/LFS), they have a one in four chance of producing a foal that gets Arabella’s defect copy (LFS) and also Bartolomeo’s defect copy (LFS), making its genotype (LFS/LFS) leading to the clinical symptoms of LFS.

However, if Arabella (clear/LFS) is bred to stallion Cartago who is not a carrier (clear/clear), the foal again gets one of Arabella’s copies (either clear OR LFS) and one of Cartago’s copies (clear either way). This means it has a 50% chance of being a carrier (clear/LFS) and a 50% chance of being completely free of the disease (clear/clear). Most importantly, the foal has a 0% chance of developing LFS.

This means if you breed Arabella, knowing that she is a carrier, it is very important to check that the stallion is not. If you breed a mare that has two clear copies, it is less relevant which stallion she is bred to. Similarly, if you breed a mare to a carrier stallion like Bartolomeo (clear/LFS), it is important to know her status, whereas if you want a foal from a clear stallion like Cartago (clear/clear), it is less important. To improve the genetic health of all Arabian horses, the long-term goal should be the complete elimination of the gene for LFS by only breeding from clear horses.

Diagnostics

The easiest way to test both mares and stallions is by DNA test. The form for this test is available from the Arabian Horse Society of Australia (www.ahsa.asn.au/genetic-disorders) and only requires mane or tail hair with attached hair follicles. The cost currently amounts to $45 per horse, which is infinitely less than the financial and emotional costs of a dead foal. Combination packs with testing for other genetic diseases, such as Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder (SCID) and Cerebellar Abiotrophy (CA) are available and listed on the website.